UCR 進行了一項非常有趣的研究,比較美國流行童書與中文童書的分別,原來兩者看重和強調的人生觀很不一樣呢!

What are the hidden messages in the storybooks we read to our kids?

That’s a question that may occur to parents as their children dive into the new books that arrived over the holidays.

And it’s a question that inspired a team of researchers to set up a study. Specifically, they wondered how the lessons varied from storybooks of one country to another.

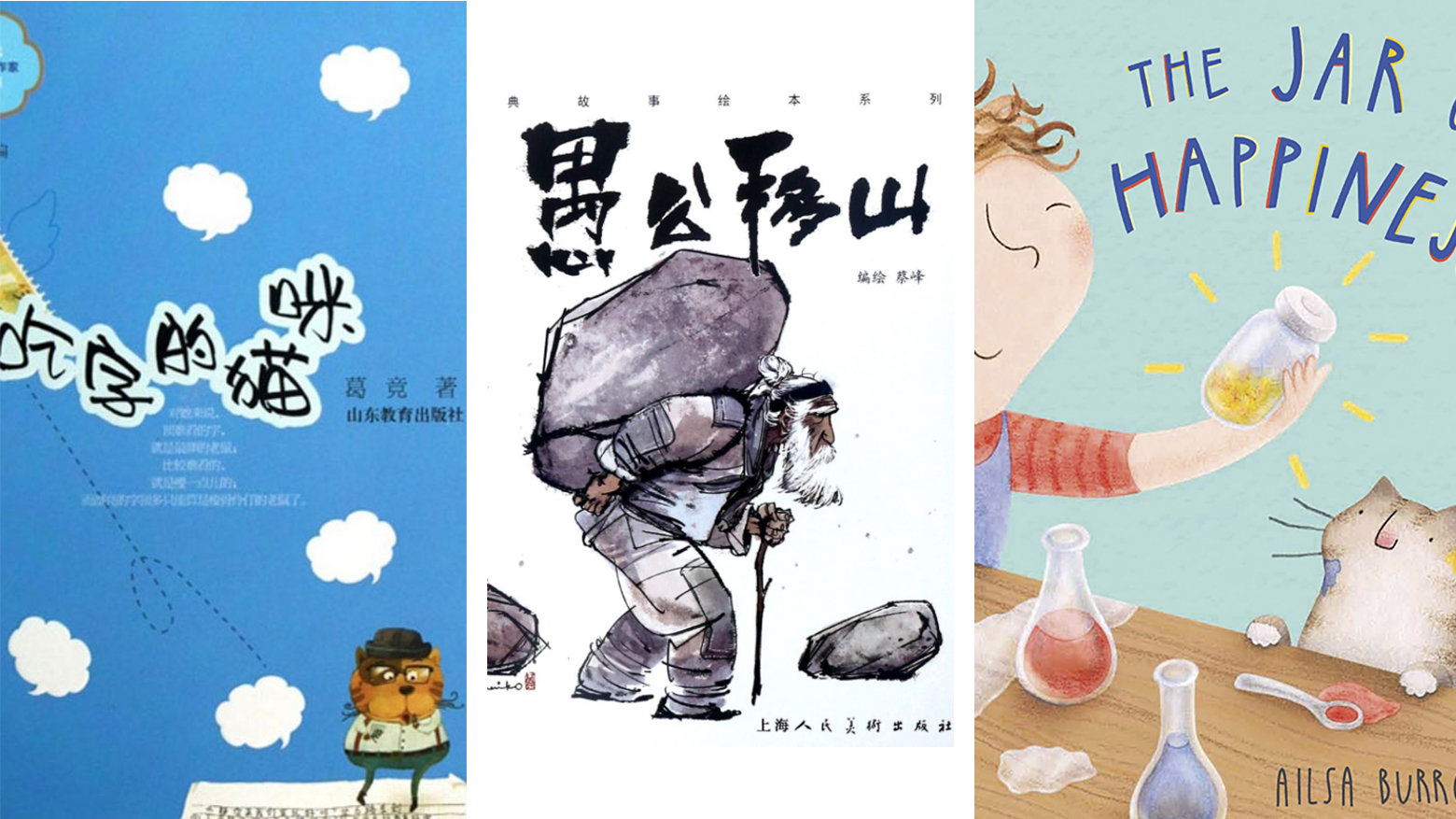

For a taste of their findings, take a typical book in China: The Cat That Eats Letters.

Ostensibly it’s about a cat that has an appetite for sloppy letters — “written too large or too small, or if the letter is missing a stroke,” explains one of the researchers, psychologist Cecilia Cheung, a professor at University of California Riverside. “So the only way children can stop their letters from being eaten is to write really carefully and practice every day.”

But the underlying point is clear: “This is really instilling the idea of effort — that children have to learn to consistently practice in order to achieve a certain level,” says Cheung. And that idea, she says, is a core tenet of Chinese culture.

The book is one of dozens of storybooks from a list recommended by the education agencies of China, the United States and Mexico that Cheung and her collaborators analyzed for the study.

They created a list of “learning-related” values and checked to see how often the books promoted them. The values included setting a goal to achieve something difficult, putting in a lot effort to complete the task and generally viewing intelligence as a trait that can be acquired through hard work rather than a quality that you’re born with.

The results — published in the Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology: The storybooks from China stress those values about twice as frequently as the books from the U.S. and Mexico.

Take another typical example from China — The Foolish Old Man Who Removed The Mountain, which recounts a folktale about a man who is literally trying to remove a mountain that’s blocking the path from his village to the city.

“Every day he has to dig some dirt from the mountain,” says Cheung.

The book celebrates perseverance, of course — but also another value Cheung and her collaborators tracked: steering clear of bad influences. As Cheung puts it, “avoiding a negative person and staying on track and not being distracted by things that would derail you from achieving your goals.”

In this case the man keeps on digging “even as he has to endure criticism from his fellow villagers who call him silly. And in the end he actually removes the mountain.”

By contrast, Cheung says a typical book from the U.S. is one called The Jar of Happiness.

“A little girl attempts to make a potion of happiness in a jar,” explains Cheung. Only to lose the jar. She’s really upset — until all her friends come to cheer her up. “At the end of the story she comes to the realization that happiness does not actually come from a jar of potion but from having good friends.”

Cheung says this emphasis on happiness comes up a lot in the books from the U.S. In some cases it’s overt – central to the plot of the story. But often it’s more subtle.

“They’ll just have a lot of drawings of children who are playing happily in all sorts of settings — emphasizing that smiling is important, that laughing is important, that being surrounded by people who are happy is important.”

The same held true of the books from Mexico.

“They’re just not so focused on the importance of achieving a particular goal or persisting so that you can overcome an obstacle. Those are much more emphasized in the storybooks from China.”

What are the implications?

Cheung notes that children in China consistently score higher on academic tests compared to children in the U.S. and Mexico. But she says more research is needed to determine how much of that is due to the storybooks or even to the larger differences in cultural values that the books reflect. Other completely unrelated factors, such as different teaching techniques could be at work.

In the meantime, Cheung says her study suggests all three cultures might have something to learn from each other.

For instance American parents might want to take a cue from Chinese storybooks and supplement their children’s reading with more tales that promote a view of intelligence as changeable.

After all, says Cheung, if you think intelligence is gained through effort, then when you’re confronted with a challenge or even an outright failure, “you just put more effort into it. You try to learn from the experience and you think about different ways of approaching the problem rather than saying, ‘No, I’m just not smart and I’m just going to give up right away.'”

Conversely, Chinese parents might want to learn from the American focus on encouraging children’s happiness and sense of connection to others. “This is something that’s really important to instill in children,” she says. “And happiness is also important when it comes to learning. It can be a predictor of future achievement.”

And lest you’ve been worrying about the fate of that cat — Cheung has reassuring news. Once the kids improve their handwriting, “the cat feels very hungry,” says Cheung. But then the kids take pity on him — and write a few sloppy letters for him to eat.