Babies on airplanes. It's enough to make parents—and all the passengers around them—cry.

Parents are complaining of airline seating policies that create "baby ghettos" in the back of planes. Even worse, families are increasingly split up, leaving small children in middle seats in the company of strangers unless passengers arrange seat swaps on board.

Michael Lyon booked seats together for his family for a trip from Washington, D.C., to Bangkok on United Airlines in July and checked his reservation frequently to make sure the seat assignments didn't change. But when he checked in, all three had been split up, and his 6-year-old son was moved to the back of the wide-body plane by himself for the 13-hour trip.

A United gate agent told Mr. Lyon there were no seats and nothing could be done. He protested, ultimately getting a supervisor who found two seats together so he could sit with his son. "Not only did the United gate staff not seem to understand the importance of having him next to us, they were hostile," Mr. Lyon said.

Even during peak holiday travel periods, adults, of course, outnumber children on planes, and airlines have to balance the needs of parents with other passengers whose nightmare is a long, crowded flight next to a noisy child.

Several factors are at play. First, many seats on flights are reserved for elite-level frequent fliers or full-fare business travelers. Routinely full flights have less seat-assignment flexibility. Also, airlines are increasingly selling choice seat assignments for extra fees, an expensive option for families. And bulkhead rows at the front of coach cabins that used to be ideal for traveling with infants, offering more privacy for diaper changes and more space for restless toddlers, now have to be reserved for passengers with disabilities. As a result, families often end up separated or at the back of the plane.

In Mr. Lyon's case, United says its systems are set up to keep groups together, but his seat assignments may have been altered because of a change in aircraft for his trip. After he complained, including sending United the names of passengers who witnessed the confrontation, the airline said it conducted an investigation and apologized to him.

Baltimore mom Teresa Toth-Fejel flies AirTran occasionally and has been told by airline agents that if she wants seats together with her kids—ages 1, 2 and 6—she should pay extra for reserved seat assignments. She sets alarms for 24 hours before departure to check-in online. "I'm so freakishly worried about it," she said.

When that doesn't work, she has been able to take the free seat assignments in different rows and trade with willing fellow passengers—who likely don't want to be caring for a toddler on their own.

"I feel like it's discrimination against families. For us, it is not an option to not be by my 2-year-old," she said.

Summer Smith Hull, who blogs about frequent-flier miles for families, checks over and over for seat assignments if she doesn't get them right away, grabbing seats that open up when travelers cancel or get upgraded to first class. "The No. 1 way you set yourself up for trouble is if you go to the airport without seat assignments," she said. A recent flight didn't have seat assignments, so she kept calling the airline until she finally got seats.

Adding to the complexity: Several airlines, including American and United, don't let travelers add children flying free on a parent's lap to reservations online. Instead, they must call the airline or get an airport agent to add a lap child to their reservation. Southwest Airlines requires taking a lap child to a ticket counter with a birth certificate on the day of travel to verify the child is younger than 2 years old.

The plane's configuration can also affect placement. On smaller regional jets, for example, some rows don't have an extra oxygen mask to be used on an infant traveling on an adult's lap. That means someone who reserved a seat and has a lap child must be relocated, splitting up a family. (SeatGuru.com has information about location of oxygen masks.)

For their part, airlines say they try to keep families seated together, encourage gate agents to rearrange seating to accommodate families and still provide some kid-friendly amenities. While microwave ovens have been removed from many planes since airlines no longer serve hot food, carriers say flight attendants still warm bottles with hot water. Wide-body jets still have diaper-changing areas.

American recently installed new software that attempts to seat together families with children 12 years and younger who don't have seat assignments 72 hours before departure, significantly ahead of most other customers.

American recently installed new software that attempts to seat together families with children 12 years and younger who don't have seat assignments 72 hours before departure, significantly ahead of most other customers.

Other carriers suggest families should pay for seat assignments to make sure they stay together since it's harder to get seat assignments in advance, free of charge. US Airways has no restrictions on families reserving seats in advance, but "we do encourage families to take advantage of Choice seats to ensure seating together," a spokesman said.

Overall increased stress of travel due to luggage charges and security procedures has made travelers less tolerant of kids, some parents say.

"Sometimes other passengers are willing to help you out. But others look at you like you are the devil for bringing a child on an airplane," said Alecia Hoobing, who works for a technology company from her home in Boise, Idaho. The evil eyes are more acute when families upgrade to first class, she and Ms. Hull agree. Malaysia Airlines decided this year to ban babies from first-class cabins of its Boeing 747 jets and next year in its new Airbus A380 super-jumbos because of passenger complaints of crying children in the expensive seats.

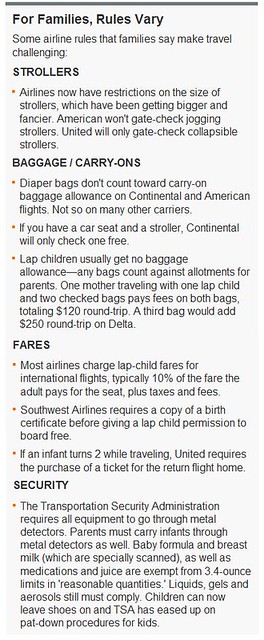

Ms. Hoobing thinks the hardest part of travel with kids is boarding. Airlines typically no longer let families with small children board first on flights. Instead, they often come after first class and top-tier frequent fliers. Kids and parents—lugging car seats, diaper bags, videogames and toys—clog the aisles and delay general boarding. Though airlines provide leniency, such as exempting diaper bags for carry-on bag limits and waiving checked-baggage fees for car seats and strollers, they have tightened restrictions.

On June 1, for example, American stopped letting parents check jogging strollers, non-collapsible strollers or strollers heavier than 20 pounds at the gate. United already bans gate-checking strollers that don't collapse.

source: Wall Street Journal